The current COVID-19 pandemic has raised concerns about the widespread implementation of protectionist trade policies. The global nature of this health crisis has led to exceptional government measures, such as the confinement of the population in their homes and the prohibition of the movement of people between countries. As a result, a significant part of countries’ productive and commercial activity to date is suspended. In this connection, the disruption of global economic activity has led to a greater shortage of certain resources required by health and social assistance systems to deal with the crisis, as well as essential goods such as food. Broadly speaking, as Legrain (2020) points out, the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the perception of international mistrust, a suspicion affecting both individuals and institutions and the international trading system, which could shape trade policy positions both today and after the pandemic. Then, could the current crisis promote protectionist trade policies?

Although countries have been taking certain trade measures in response to the current context, the trade policy position to be assumed by the world’s governments as a result of the crisis remains to be seen. A historical reference period that can give us light on what might happen in the field of trade policy is the first quarter of the twentieth century. Among the global events that occurred at the time is the pandemic caused by the H1N1 virus between 1918 and 1920, which has also been known as the Spanish flu or the 1918 pandemic. As Barro, Ursúa, and Weng (2020) point out, what happened during that historic episode can be considered the worst possible case to which the COVID-19 pandemic can be compared. According to their estimates, this pandemic killed approximately 2% of the world’s population at the time (39 million people) and caused an average reduction in the real GDP per capita of the affected countries by 6%. Although the current crisis is unlikely to acquire a similar magnitude to that of 1918 in terms of the number of deaths, given the current availability of better-equipped health services, the situation then may be useful in helping us understand the current situation.

In this connection, what can be said about the trade policy implemented before, during and after the 1918 pandemic? Although the availability of data related to that period is less than the volume of existing information on more recent events, there are certain Charts that may give us some initial responses. Consider, first, the evolution of trade between 1900 and 1938 (just before World War II). As shown in Chart 1, from the beginning of the twentieth century to 1920, world trade activity showed a more or less stable growth. According to calculations based on data by Fouquin y Hugot (2016), despite the occurrence of World War I, which affected European trade significantly, world trade managed to increase from approximately US$ 3,490 million to approximately US$ 15,278 million in 20 years. Broadly speaking, all regions of the world reported a substantial pace of trade growth, recording average growth rates of more than 5% per year. However, this trend began to reverse from 1921 on. With the exception of Oceania, all regions of the world had average trade growth rates below -2.5% per year between 1920 and 1938, which explains the decline in world trade from approximately US$ 15,278 million to approximately US$ 7,113 million. These movements account for a possible change in pattern in trade policies in 1920, the year in which the 1918 pandemic ended.

Chart 1

Evolution of world trade, 1900-1938

Source: Fouquin and Hugot (2016), own calculations.

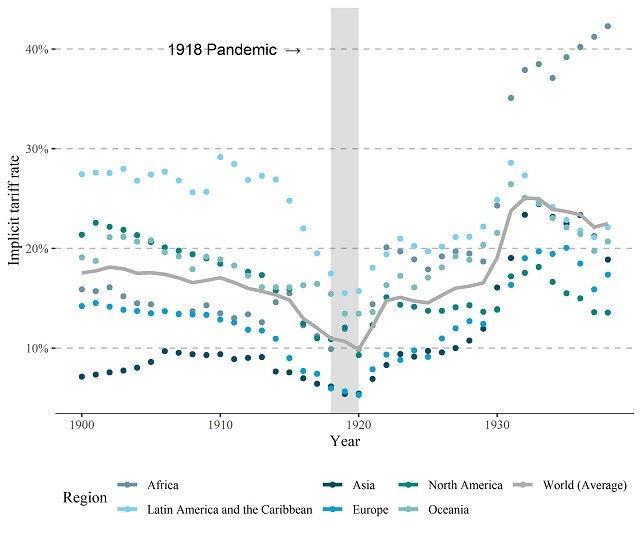

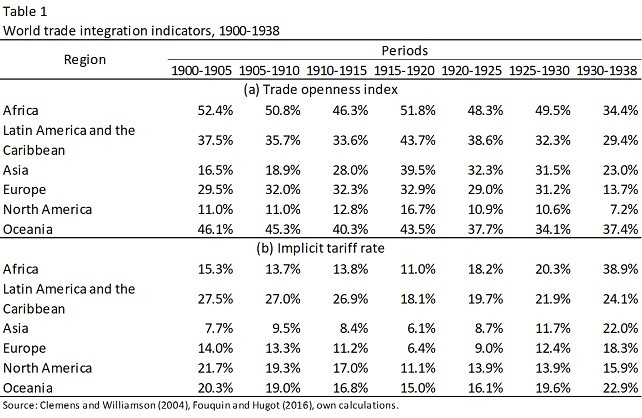

Now, consider the implicit tariff rate then, which can give us a closer approximation of the trade policy positions at that time. As shown in Chart 2, the world tariff rate followed a strong pattern towards trade liberalization until 1920, when it reversed significantly in favour of protectionism. According to calculations based on estimates by Clemens y Williamson (2004), between 1900 and 1920 the world tariff rate fell from approximately 17.53% to 9.85%, but then rose to 22.49% in 1938. While there were disparities among countries in tariff rates applied, their movement followed the same pattern as that evidenced for the global average, which gives an account of the strategic nature of trade policy decisions. These patterns are consistent with the trade openness index set out in Table 1, which shows that, in general, the trend towards trade openness changed after 1920.

Chart 2

Evolution of the world tariff rate, 1900-1938

Source: Clemens and Williamson (2004), own calculations

Apart from the possible impact of World War I on the trade policy change, the 1918 pandemic may have played a significant role in this regard. This impact could also have occurred in two stages. In theory, as a result of the reduction in economic activity caused by a pandemic, country governments appear to have no incentives to take measures that limit imports in the short term, as it is necessary to meet urgent basic needs that the domestic economy cannot assume. However, after a pandemic, country governments will recognize losses in local productive capacities resulting from the health emergency, which, along with a climate of international mistrust resulting from global transmission of the disease, may promote the establishment of trade protection measures.

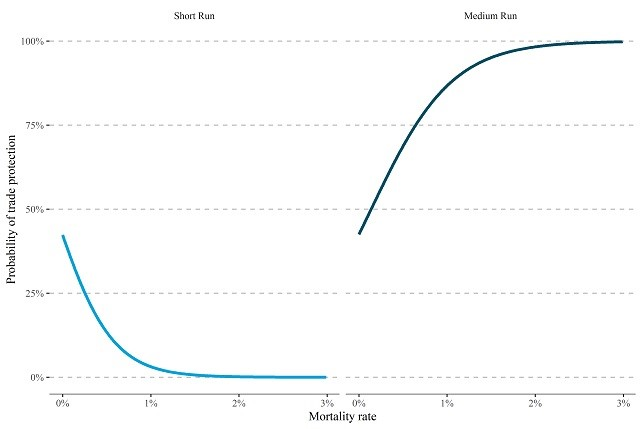

This relationship between the occurrence of a pandemic and trade policy decisions could be verified with data related to the 1918 pandemic. Preliminary results of a research, which is being conducted by the author of this paper, suggest that the likelihood of taking trade protection measures tends to be reduced during a pandemic in the short term, but after two years that likelihood tends to increase significantly. As shown in Chart 3, an increase in the severity of a pandemic, measured by the mortality rate attributable to the disease, is associated with a rapid reduction in the likelihood of increasing trade protection in the short term. However, in the medium term this probability is not only reversed but increases rapidly in relation to the severity evidenced by the pandemic in previous years. This suggests that this situation is highly likely to recur in the current circumstances.

Chart 3

Probability of trade protection vs. mortality rate of a pandemic

Source: own calculations.

Given the current COVID-19 crisis, the experience of the 1918 pandemic seems to show us a not very encouraging picture for years to come. Attention to an overall increase in trade protection will require cooperation among States through existing institutions in this area. Therefore, the role of the World Trade Organization and other multilateral agencies relating to international trade will be relevant to promote an agenda of solutions that prevents a rise in protectionism and, consequently, the losses of social welfare associated with contexts of low or zero trade relations.

References

Barro, Robert J., José F. Ursúa, and Joanna Weng. 2020. «The Coronavirus and the Great Influenza Pandemic: Lessons from the “Spanish Flu” for the Coronavirus’s Potential Effects on Mortality and Economic Activity». Working Paper 26866. Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w26866.

Clemens, Michael A., and Jeffrey G. Williamson. 2004. «Why did the Tariff-Growth Correlation Change after 1950?» Journal of Economic Growth 9 (1): 5-46. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOEG.0000023015.44856.a9.

Fouquin, Michel, and Jules Hugot. 2016. «Two Centuries of Bilateral Trade and Gravity Data: 1827-2014». Working Paper 2016-14. Working Papers. CEPII research center. https://ideas.repec.org/p/cii/cepidt/2016-14.html.

Legrain, Philippe. 2020. «The Coronavirus Is Killing Globalization as We Know It». Foreign Policy (blog). 12 de marzo de 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/03/12/coronavirus-killing-globalization-nationalism-protectionism-trump/.