Fresh from a $5.25 billion, nine-year expansion that’s upending decades-old trade routes, it turns out the Panama Canal is also doing a little good for the planet.

By offering a short-cut to deliver billions of dollars of Asian-made goods to America’s East Coast ports, the waterway has helped its shipping company customers to lower their collective carbon emissions by 17 million metric tons during the first full year of operation. When the expansion was planned, the authority’s internal forecast was 9.6 million tons, according to Alexis Rodriguez, environment protection specialist at the Panama Canal Authority.

For Panama, successfully combating climate change could be pivotal to the country’s future. The canal is filled by waters that have flowed for centuries down from the country’s mountains. There have been times in the past few years when low water levels forced the canal to impose minor restrictions on the ships it allowed through.

“If we don’t take measures to cut pollution then we will all suffer in our pockets,” Rodriguez said in an interview in London, where he was attending a meeting of global governments to discuss the shipping industry’s contribution to combating climate change.

Read more: how expansion of the canal redrew trade routes

As well as helping Asian manufacturers to deliver goods to the U.S. east coast faster, the widened canal has redrawn commodity trade routes. America’s booming energy supplies -- particularly liquefied gases and even oil -- are flowing in the opposite direction like never before. The link can also be used to haul iron ore, coal and grains to Asia from places like Brazil, Colombia and Argentina.

Shorter journeys, better ships

The boost to the environment comes from the fact bigger, more efficient ships are now going through. Critically, they can shave thousands of miles off journeys, meaning they consume much less fuel.

Panama’s support for tougher environmental rules for shipping, which also includes promoting limits on sulfur emissions, stems partly from a desire to avoid any longer-term threat to the canal’s water levels, Rodriguez said.

The authority now expects its customers to save about 320 million tons of CO2 in the first decade of the expanded operation, said Rodriguez. That’s about double the amount it anticipated when the expansion was planned. It’s also about the same as Spain’s annual emissions.

He spoke as more than 200 government and industry representatives met in London to discuss how to cut carbon emissions from shipping operations to zero by the second half of the century, down from as much as 3 percent of global emissions now. They met at the International Maritime Organization, the United Nations’ shipping agency.

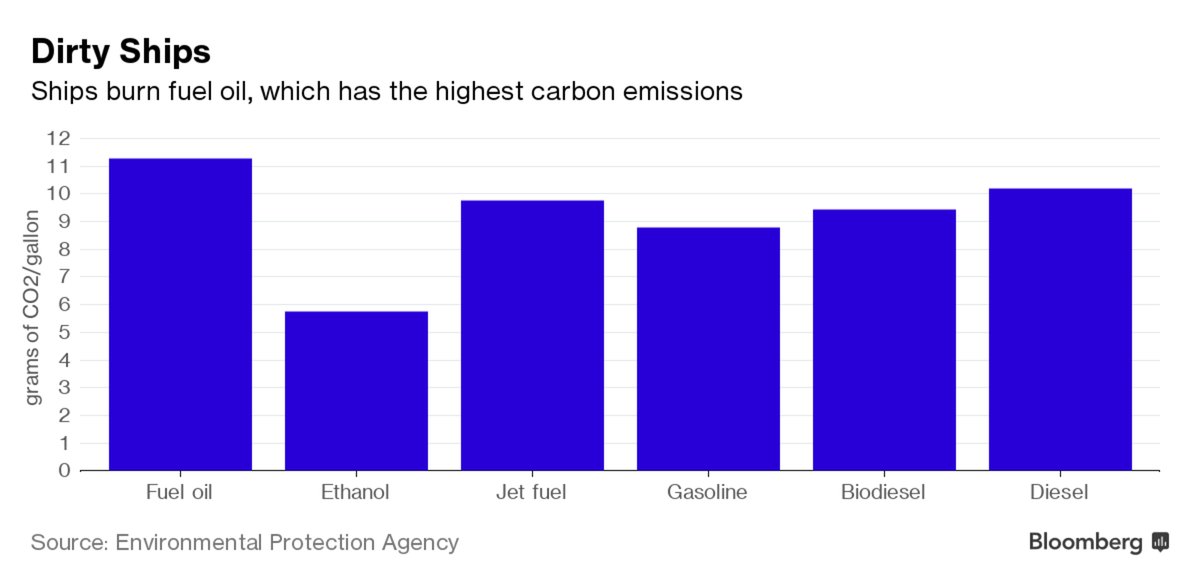

Imposing mandatory emissions rules would close a loophole left by the 2015 Paris climate agreement. Ships engaged in international maritime trade mostly burn heavy fuel oil, one of the dirtiest and cheapest forms of energy. IMO members will return to discuss their levels of ambition in October and an agreement could be drafted by next year.